Jonas Nesselhauf: She Said. The »#MeToo« discourse, its narratives and fictional transformations, 2017–2021

Abstract: As every other discourse, the global »#MeToo« movement is centered around specific narratives and counter-narratives: With the »Weinstein effect« soon reaching beyond Hollywood, the hashtag has raised widespread awareness for the ubiquity of everyday sexism in patriarchal societies over the past four years—but the digital activism was also countered by anti-feminist backlash. At the same time, early European and North American novels and films have now also taken up the subject and developed their very own narratives: Within the fictional space, for example, the narrative focus gives voice to female experiences, the stories reflect the potential of female empowerment, can play with metafictionality or critically depict the ›other side‹.

Keywords: MeToo, feminism, activism, rape culture, narratives, literature, film, performance

It has now been about four years since a global movement under different names emerged and constituted a historic turning point: Using hashtags such as »Me Too«, »Time’s Up«, or »Balance ton porc« countless women have identified themselves in the autumn of 2017 as being personally affected by sexual violence.

What originally started as a celebrity sex scandal with accusations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein has not only led to the arrests and convictions of many public figures in the months and years to come, but has also caused wider and, frankly, more basic discussions concerning everyday sexism as well as physical and sexual violence against women, concerning gender roles and relations, and concerning diversity and equality.

Also, both mass protests as well as single women speaking out on social media have shed light on failing justice systems which not adequately address rapes and femicides, when cases are dropped by police and district attorneys (DAs), and traumatized victims are blamed for the sexual assault.

Besides North America and Europe, the movement has also become a watershed moment for many patriarchal societies in which assault and harassment have become a part of everyday life, including India and South Africa—and even in Russia or China, the outcry of women has made waves.

And while the impact of the »#MeToo« movement is still present to this day, the last four years also saw many innovative approaches in literature and film. Here, within the fictional space, the various narratives and counter-narratives of the »#MeToo« discourse are discussed, played through and weighed against each other. Due to their graphic nature, novels, stories or films can thus make both crucial problems as well as implicitly suggested solutions more comprehensible to a broad audience—and can as an inter-discourse, in turn, have an effect back into society.

1. Call-out-culture

multiple incidents of sexual harassment and physical abuse due to power imbalances have been made public over the last decades—and some cases actually led to criminal investigations and/or convictions of public figures—, prior to 2017 there was no social movement with such a global and media influence as the new type of anti-sexual violence activism known as »#MeToo«. Instead, problematic behavior by powerful men was either belittled as ›gallantry‹ or dismissed as a political smear campaign, for instance with Anita Hill’s 1991 allegations of sexual harassment against federal judge Clarence Thomas or with the 1998 political scandal involving US president Bill Clinton and White House intern Monica Lewinsky (sometimes even downplayed as an ›affair‹). In Clinton’s case, for instance, his blatant lie—»I did not have sexual relations with that woman«—quickly became a standard saying in the US,1 thereby further trivializing the actual incident. When a few years later Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund and a potential candidate for the upcoming French presidential election, was arrested in New York City and charged with the sexual assault and attempted rape of a hotel maid in May 2011, many colleagues supported him immediately, thus ranking the legal principle of the presumption of innocence higher than the accusations of a possible victim.2 Being public figures, the perpetrators very often had to fear no serious consequences, and the accusations quickly became a ›he said, she said‹ case, in which the less powerful woman almost automatically is discredited or victim blamed—especially if she has waited weeks, months or even years until confiding in another person or reporting the incident to the police.

The turning point can be dated exactly to 6 October 2017, when a first New York Times story by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey of Weinstein’s alleged harassment and abuse broke (Kantor/Twohey 2017); a few days later, Ronan Farrow’s article »From Aggressive Overtures to Sexual Assault« was published by the New Yorker (Farrow 2017a; 2017b). The ›pattern‹ of Weinstein and others was exposed: Powerful men in showbusiness harass and assault young women looking for a future career—mainly promising actresses or eager assistants (Kantor/Twohey 2019, p. 73)—, while their wrongdoing is systematically covered up by the networks and companies behind them, and the victims are forced to sign nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) in exchange for a payout (Farrow 2019, p. 375f.). As further allegations surfaced and more victims, including famous Hollywood actresses, came forward over the next days, Weinstein was fired from his production company and expelled from the Motion Picture Academy. Using the Twitter hashtag »#NoShameFist«, actress Asia Argento posted a list of more than 100 women who have accused Weinstein of sexual harassment, physical assault or rape with incidents dating back to the early 1980s.3

The »Weinstein effect« (Guynn/della Cava 2017), as it was soon called, »was a solvent for secrecy, pushing women all over the world to speak up against similar experiences. The name ›Harvey Weinstein‹ came to mean an argument for addressing misconduct, […] an emerging consensus that speaking up about sexual harassment and abuse was admirable, not shameful or disloyal« (Kantor/Twohey 2019, p. 181). A global movement gained momentum and held famous and powerful men responsible for their predatory behavior, including public figures such as comedian Bill Cosby (convicted in 2018) and television executive Les Moonves (resigned in 2018), senator Al Franken (resigned in 2018) and New York governor Andrew Cuomo (resigned in 2021). In some cases, consequences were long overdue—when, for example, the first allegations against photographer Terry Richardson or singer R. Kelly dated back many years and even decades; other cases reached far beyond the actual subject, for instance with multiple members of the prestigious »Svenska Akademien« resigning over accusations against Jean-Claude Arnault, eventually leading to the postponement of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature. Additionally, some revelations also shed light on sexual violence against men, with allegations against actor Kevin Spacey, starting in 2017, or against countertenor David Daniels in 2019; and even one of the movement’s leaders, Asia Argento, faced claims of sexually assaulting a minor in 2018 (»Ein Jahr danach«: 10).

After mainly famous women came forward and spoke out against powerful men in showbusiness, politics and the arts, the next step was the denouncement of power abuses in other industries, thereby ›opening‹ the discourse to ›ordinary‹ women all around the world. Besides the press coverage, social media in particular played a crucial role in sharing personal experiences and thus developing a movement—for instance when French journalist Sandra Muller tweeted on 13 October that »95% des femmes qui dénoncent des violences perdent leur emploi. La peur doit changer de camp. #balancetonporc. Pas de délation juste la vérité«.4

Two days later, actress Alyssa Milano used the slogan »me too«—a phrase already coined in 2006 by activist Tarana Burke with her MySpace page »to promote empathy and healing for victims of sexual violence« (Kantor/Twohey 2019: 185)—to raise awareness for the ubiquity of sexual assault. She posted: »If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ›me too‹ as a reply to this tweet«,5 and within hours, countless women all over the world stood up and responded either with their own stories or with a simple ›me too‹.

1.1 The power of a #hashtag

The global real time of the internet and the possibilities of social media platforms proved that sexual harassment neither has been limited to an obviously sexist film industry nor that it is an elite (white, heterosexual) phenomenon or only affects famous or rich women, actresses or politicians. Instead, it painfully shows that it is a general problem and basically concerns every woman who has ever faced groping or harassment in the workspace, who was catcalled or hustled in public places, or who was sexually abused or even raped: Data suggests that up to 85 percent of women in the US will experience sexual harassment at work during their careers (Lhamon et al. 2020: 1), with the perpetrators being predominantly male—findings that are supported by an analogous EU-wide survey (Kjaerum et al. 2015: 113).

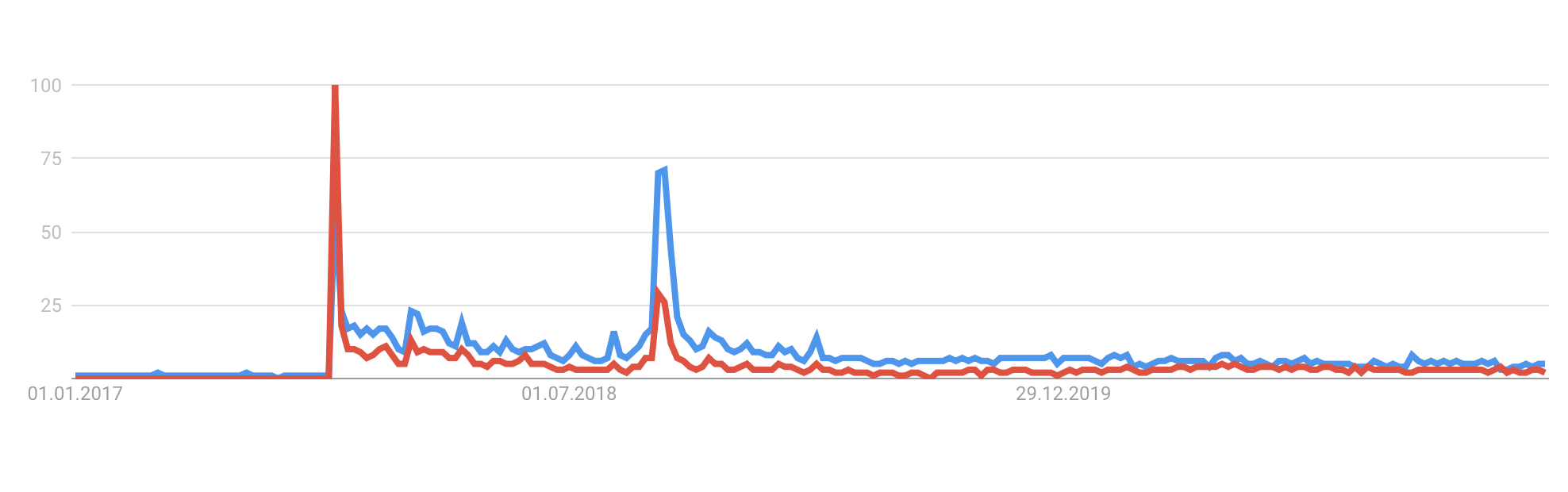

And while European and North American studies—astonishingly or shockingly—tend to have similar results (Schröttle et al. 2019: 31–40), the women coming forward were not just a number in a statistic, but provided actual cases and individual, traumatizing stories: Within 24 hours after Milano’s initial tweet, 4.7 million users from all around the world engaged in the »#MeToo« conversation, with over 12 million posts, comments, and reactions on Facebook alone. Besides the English »#MeToo«, the Spanish »#YoTambien« as well as the hashtags »وأنا_كمان#« and »وانا_ايضا#« in Arab countries were trending on Twitter (Khomami 2017). And on Google, search queries increased rapidly in the third week of October 2017, with another spike around the first anniversary of the Weinstein revelations (Fig. 2).

Soon, the hashtag took on a life of its own and quickly gained a mainstream popularity, when the issues raised by »#MeToo« exceeded the Weinstein case and instead questioned traditional notions of masculinity and male behavior in general: While about half of the tweets in the first two weeks were disclosures of sexual violence, in which (mainly female) Twitter users revealed information or shared personal experiences, the other half already included wider discussions of sexual violence and its impact on society (Gallagher et al. 2019: 8f.).

However, the attention was not without its drawbacks, since indeed »the power of the Weinstein moment came from the victims of abuse having space to name the abuser—and to have their words taken seriously« (Press 2017), but was mainly »popularized by the white and the wealthy« (Kindig 2018). Tarana Burke, for instance, feared that ›her‹ hashtag—introduced in 2006 to draw attention to the sexual assault of Women of Color—could end up getting ›whitewashed‹ (Adetiba 2017). Similarly, others demanded that the focus of Hollywood initiatives such as »Time’s Up« should be on low-wage women and marginalized communities, who are especially exposed to sexual harassment and intersectional discrimination.

The digital activism also led to discussions about whether ›disgraced‹ artists and their works should be morally and artistically reconsidered: At first with a focus on directors, actors, comedians or artists such as Roman Polanski, Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K, or Chuck Close, this reassessment soon expanded to a proper canon critique that exposed sexist representations, such as paintings by Balthus or photographs by David Hamilton, and scrutinized problematic production situations, for instance filmic depictions of rape in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970) or Bernardo Bertolucci’s Ultimo tango a Parigi (1972). As critically acclaimed as the performances were and actually may be, many argued that the films »have been shaped by those actions« and ultimately »affected the paths of other artists, determining which rise and which are harassed or shamed out of work« (Hess 2017).

1.2 »#MeToo« Counter-Narratives

But the »#MeToo« discourse also sparked a lot of (expectable) backlash among conservative and anti-feminist activists, and until today the movement sometimes still is rejected as a left-wing agenda, an ideological ›campaign‹ attacking free speech through ›political correctness‹. The narratives used to counter the movement included, among others, a reversal of the accusations by blaming the victims, a defense of male gallantry, and a general criticism of networked feminism.

1.2.1 Career Women

Interestingly, women breaking their silence and standing up in a collective protest against sexual violence was not always regarded as both an empowerment for the individual as well as a necessary step forward in overcoming patriarchal structures. Instead, some people argued that »#MeToo« as a belated retaliation would rather create an image of women characterized by negativity and passivity (Flaßpöhler 2018: 16). Others engaged in a questionable victim-blaming, belittling the Hollywood actresses coming forward, since supposedly ›everyone knows the rules of the casting couch‹ (Kantor/Twohey 2019: 73).

Accordingly, the strategy of Weinstein’s defense lawyer Donna Rotunno was not a surprise, making the long-awaited trial of the Hollywood mogul a proper »battle of tropes: the casting couch versus the woman sleeping her way to the top« (Nicolaou 2020: 1): Besides challenging the testimonies of the alleged victims, Rotunno tried to portray the encounters as consensual relationships and emphasized that it was in fact the women approaching Weinstein, because they wanted something from the film producer (Nicolaou 2020: 2). This argument follows a ›classic‹ pattern, when women coming forward and even testifying publicly under oath—such as Anita Hill in 1991 or Christine Blasey Ford in 2018—are regularly deemed ›not credible‹, because they did not initially report their assault or (in the case of Hill) later even took a second job from their perpetrator (Kantor/Twohey 2019: 190f.). Similarly, for instance, the lawyers representing David Daniels stated in their first comment that the alleged victim »waited eight years to complain about adult, consensual sex« (qtd. in Cooper 2019: C3), thus disregarding that victims of sexual harassment might feel embarrassed or ashamed, might even blame themselves for the incident, or were in fear of workplace retaliations for speaking up (Press 2017).

In other cases, the naïveté of women who were, for instance, willing to join male colleagues or supervisors in their hotel rooms, was criticized, hence tracing back guilt and responsibility to the actual victim—instead of asking how women can be better protected from gender inequality and power imbalances (Cobb/Horeck 2018). After all, the discussion is far from being new: As early as around 1980—and hence, in retrospect, at a time when many of the assaults by Weinstein and others happened or started to happen—, political activist Angela Davis already remarked that »sexual assault is explosively emerging as one of the telling dysfunctions of present-day capitalist society« (Davis 1981: 172), and feminist Susan Brownmiller demanded a »gender-free, non-activity-specific law governing all manner of sexual assaults« (Brownmiller 1975: 378).

1.2.2 Rape Myths

Probably one of the most prominent »#MeToo« cases in Germany included accusations against the television and theater director Dieter Wedel, brought forward by several actresses in January 2018 by the Zeit newspaper (Simon/Wahba 2018a; 2018b). Although most of the alleged incidents are legally time-barred, his legal defense team—which consists, among others, of a former federal judge at Germany’s highest criminal court as well as a conservative politician—generally dismissed the accusations as »Lynch-Stimmung« and a »widerrechtliche[] Vorverurteilung« (qtd. in Backes/Hipp 2021: 44).

Arguments like these suggest that wrong assault charges might be filed deliberately in order to ›hunt down‹ powerful men, thus reproducing the misogynistic idea that »men are the victims of spiteful women« (Gordon 2018). And while such false statements happen very rarely—and a lot of cases are actually dismissed for want of evidence with very low reporting and conviction rates at all—,6 their effects can be dreadful in both intensifying other victims’ fears that their accusations will eventually not be believed and thereby publicly shaming an innocent person (Srinivasan 2021: 9f.).

Hence, the digital activism of »#MeToo« was indeed criticized for the rush to prejudgment on social media’s so-called ›court of public opinion‹ (Sanyal 2019: 178): Instead of a proper trial and the guarantee of due process and a legal defense, the digital ›pillory‹ hardly differentiated between minor and major offences at all (Flaßpöhler 2018: 17f.).

But there was also an even grimmer pushback against the women coming forward when the sexual assault (of whatever degree) was not actually denied, but rather, conversely, blamed on the victims’ behavior (initial flirting, intoxication, etc.) or even clothing:7 This ›classic‹ narrative, established already long before »#MeToo« and used especially against women, argues to simply ›not wear those (too revealing) clothes‹—as for instance expressed in the title of Birgit Kelle’s essay Dann mach doch die Bluse zu (2013), an anti-feminist backlash to the German »#Aufschrei«.8

1.2.3 ›Boys will be boys‹

Gillette, the Boston based safety razors company, launched its 2019 advertising campaign right in time for the Super Bowl LIII, where television commercials with costs up to five million dollars for a 30-second spot promised a high and demographically widespread viewership. However, their short film »The Best Men Can Be«[1] almost immediately generated controversy and was highly criticized for both its ›purplewashing‹ and ›femvertising‹ (Hausbichler 2021: 39f.) as well as for reproducing stereotypes of toxic masculinity—particularly since one of the recurring narratives in the »#MeToo« debate was insisting that predatory behavior does not reflect ›all men‹.

Additionally, this feminist criticism was countered by the (weak) excuse of male behavior towards women being a simple ›playfulness‹ of boys, especially when the accusations dated back several years: Some claimed the predators were simply not yet grown-up men, responsible for their actions back then, particularly since »#MeToo« has now ›suddenly‹ changed the rules of the game, when »no« actually means »no«.[2] And there were even grimmer questions asking »how were men to have known any better«, suggesting that »patriarchy has lied to men about what is and is not OK«, as women suddenly »enforce a new set of rules« (Angel 2021: 21).

But these seemingly naïve questions concerning what the rules and where the lines under the current ›conditions‹ at all are seem also to imply that macho and predatory behavior or even sexual harassment would have been socially acceptable before (Angel 2021: 18f.). So, instead of women, it is now apparently the ›cultural heritage‹ of flirting and gallantry that needs to be protected.

1.2.4 Saving Gallantry

After »#MeToo« had first emerged in the wake of the 2017 Harvey Weinstein sex scandal and began to expand beyond the film industry, some argued that the movement has apparently also blurred the lines: In an open letter published in the newspaper Le Monde in January 2018, 100 high profile French women demanded the »liberté d’importuner« (Collectif 2018: 20). The signees, among them actress Catherine Deneuve, author Catherine Millet and singer Ingrid Caven, stated: »Le viol est un crime. Mais la drague insistante ou maladroite n’est pas un délit, ni la galanterie une agression machiste« (Collectif 2018: 20).

However, their argument of an ultimate »Welt ohne Verführung« (Flaßpöhler 2018: 14) suggests that there are no distinctions, lumping together different forms of inappropriate and predatory behavior—be it sexist jokes or catcalling, unwanted ›dickpics‹ or stalking, flirting and seduction, men groping or ›stealing‹ kisses, unwelcome advances and requests for sexual favors, sexual harassment, assault and rape (Flaßpöhler 2018: 13)—, when instead others claimed that there actually is a difference between a man being a ›jackass‹ or a ›predator‹ (Coontz qtd. in Reese 2017).

Even after 2017, initiatives establishing a »campus consent culture« were criticized for patronizing women, and even updated Title IX guidelines implemented under President Barack Obama have been rolled back during the Trump administration (Angel 2021: 22f.). This conservative backlash promoting a problematic ›rape culture‹ stood in stark contrast to the social atmosphere when the many cases brought forward by the »#MeToo« movement instead underlined that the »time seems to be ripe for a new negotiation of the treacherous territory that is sexual violence« (Sanyal 2019: 178).

1.2.5 »Cancel Culture«

The fear of a premature censorship in the name of morality and political correctness was and is, especially in the United States, a highly controversial by-product of the »#MeToo« movement, since many commentators demanded that not only the artists but also their artworks should be cancelled from public life and the cultural canon respectively. For instance, with allegations reaching back several decades, film icons such as Woody Allen or Roman Polanski have not only become a persona non grata in the wake of the »#MeToo« movement, but also their entire œuvre is up for discussion. Similarly, there were requests to remove paintings by Balthus from major exhibitions or R. Kelly’s music from the catalogues of online streaming services. And while there has hardly ever been a consensus about separating the artists from the art, some argued that there certainly is and was no consistency in both the outcry and the effects—with different allegations against Kevin Spacey, Dustin Hoffman or Michael Douglas being also treated very differently in this so-called ›court of public opinion‹ (»Ein Jahr danach«: 10).

But the expectable criticism that the ›woke‹ call-out-culture has gone ›too far‹ certainly is reductive, since »#MeToo« first of all gives marginalized people the opportunity to raise their voices against powerful institutions or to be heard at all in a justice system that is not working properly. On the other hand, the fundamental rights of freedom of speech and presumption of innocence are weighed against each other, when accusations that appear to be insufficiently substantiated or fall in a grey area between rape and consent (for instance with claims against actor Aziz Ansari or scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson) have not led to their permanent public exclusion. And while even in the case of legally convicted sex offenders it ultimately remains an individual moral decision to continue to listen to their music or still watch their films, in other cases it is rather questionable to what extent one can speak of »cancel culture« at all—from former TV or tech executives receiving millions of dollars as payouts and settlements as part of their exit agreements (which are many times higher sums than their victims got in exchange for signing NDAs or settling sexual misconduct lawsuits) to, for instance, Louis C.K.’s 2020 stand-up special Sincerely Louis CK winning »Best Comedy Album« at the 64th Grammy Awards.

In either case, the collectively organized protests on social media were and are only possible because of the digital networking opportunities crossing national and linguistic borders. For many observers, the social networks enabling such a shared resistance (Arndt 2020: 294) are thus a key example for the strength of today’s feminism (van Schaik/Michel 2020: 314f.), while others argue that the accusations are not a ›real‹ female empowerment, since »#MeToo« would only reproduce old stereotypes with the woman being the passive object of male desire, endangered in a patriarchal society (Sanyal 2019: 177f.).

2. Fictional perspectives

The »#MeToo« movement as well as its backlash and counter-narratives were a decisive as well as a dividing moment for societies all over the world, with its aftermath reaching well into the 2020s: Both the reports and allegations of sexual assault as well as critical and anti-feminist positions—for instance by Jordan Peterson, Svenja Flaßpöhler, Daphne Merkin, Katie Roiphe or Claire Berlinski—continue to represent and reproduce a binarity of rape/consent, yes/no, man/woman or right/wrong, when instead »bodies and desire, sex and politics, freedom and violence, are much more complicated, rich, and fraught« (Kindig 2018).

However, »#MeToo« as a public discourse consists of more than the binary thinking and opposing positions leading to heated discussions, and both the ›victims‹ as well as the ›perpetrators‹ are not only defined by being a number in a statistic: So, for instance, when Chanel Miller in her memoir Know My Name (2019) reflects that her experience of being raped »makes you want to turn into wood, hard and impenetrable. The opposite of a body that is meant to be tender, porous, soft« (Miller 2020: 263), she makes her voice heard and thus provides an empowering platform for other women coping with similar trauma.

Hence, the images and metaphors used by Miller to describe her highly personal, deeply traumatic experience are—compared to other narratives about such harrowing and painful encounters—a different approach in contributing to the broader »#MeToo« discourse: In contrast to, for instance, a simple newspaper report, it is precisely the tragic authenticity and the lyrical imagery that makes her account particularly vivid and thus may resonate with a wider audience.

Since there is an obvious need for such transmissions of the arguments and counter-points discussed earlier, it usually seems to be the task of literature, film and the visual and performance arts to develop stories and images, aesthetics and narratives: Here, in the fictional space, social conflicts and problems can be acted out, immanent orders and norms can be questioned, and solutions and alternatives can be presented, with protagonists in exemplary stories showing different behavior, or rather how different behavior can be.

And while literature or film can say what has not yet been said, can show what has not been shown before, the readers and viewers are in retrospect encouraged to reflect on their own experience or behavior—even if the instruction for taking action(s) is perhaps only implied by the story itself. Thus, each and every novel or film can not only affect and activate its audience through the choice of exemplary stories and relatable characters, but with its safe distance to the fiction can also pose inconvenient questions, such as: ›What would I have done in that very situation?‹ or ›How can I protect other people from such an experience?‹. Interestingly, in comparing North American and European texts, a similar thematic focus is noticeable in the early novels and films of the first four years since »#MeToo« became a global phenomenon in 2017, with an emphasis on (a) female experiences, (b) female empowerment, (c) metafictionality, as well as (d) the ›other side‹.

2.1 Female Experiences

One of the central aspects (and merits) of a post-»#MeToo« literature has been the generalization of the female experience: Literary texts and especially short stories published only a few months after the allegations against Weinstein were first reported by the New York Times and the New Yorker, mark a paradigmatic shift in attention from the Hollywood actresses to everyday harassment. Instead of fictionalizing actual cases of prominent figures, many literary approaches (of largely female writers) are now focused on the ›ordinary‹ (young) woman, on hostile work environments, sexism and the oppression of female desire in Western patriarchal societies.

Kristen Roupenian’s short story Cat Person, first published in the 11 December 2017 issue of The New Yorker, for instance, tells the story of a short but problematic relationship between the student Margot and the 14 years older Robert: After he self-confidently asks the »›concession-stand girl‹« (Roupenian 2017: 65) out for a movie, she is confused by the mixed messages and his unstable behavior. Not wanting to hurt him, Margot finally agrees to go out for another drink afterwards—and experiences what the story’s narrative instance (with an internal focalization exclusively on Margot) reflects as »a terrible kiss, shockingly bad« (66):

By her third beer, she was thinking about what it would be like to have sex with Robert. Probably it would be like that bad kiss, clumsy and excessive, but imagining how excited he would be, how hungry and eager to impress her, she felt a twinge of desire pluck at her belly, as distinct and painful as the snap of an elastic band against her skin. (67)

Her assumptions soon become true, when Margot agrees to go home together the same night: The »huge, sloppy kisses« soon turn into an equally awkward petting, with her feeling »that she might not be able to go through with it after all« (68). Besides behaving partly clueless, partly dominant and partly frustrated during the foreplay, Robert seems obviously influenced in his behavior by mainstream pornography: In trying to fulfill the expectations of both his role as the ›active‹ and ›potent‹ man as well as of the sexual intercourse (and its series of practices and positions) itself, he projects his desire onto Margot. However, while his pornographic vocabulary initially seems rather entertaining, Margot increasingly feels »a wave of revulsion«, »self-disgust« and finally »humiliation« (69).

Although the highly unpleasant incident technically does not count as rape, not even as sexual violence in a ›classical‹ sense, comments and posts online showed the ubiquity of this story in the experiences of women worldwide: In deciding to »carry through with it« (69), Margot has to endure bad sex because she doesn’t dare to say »no« to her male partner.11

Critically praised for its psychological precision as well as for shedding light on elusive power dynamics (Baum 2019: 42), Cat Person was almost instantly spread on social networks and widely discussed in forums online: Robert’s imagination of female sexuality in general and his expectations of Margot as a sexual partner in particular seemed to stand paradigmatically for toxic male behavior and a problematic culture of non-consensual sex (Angel 2021: 66).

Published in the following year, Bettina Wilpert’s novel nichts, was uns passiert (2018) also deals with the different perceptions of a highly problematic sexual encounter, and uses the narrative technique of multiperspectivity in order to contrast the positions of the victim, the perpetrator and their circle of friends: The student Anna claims to have been raped by a fellow postgraduate, after they already had casual sex once before, whereas Jonas states that it was consensual: »Schließlich benutzte er ein Kondom. Sie wehrte sich nicht.« (Wilpert 2018: 47)

Its continuous multiperspectivity brings the novel close to a detective or courtroom plot in which different positions are juxtaposed: The narrative instance becomes more of an ethnographer (Künzel 2021: 130.), collecting these different perspectives, mostly without further comments or any form of foreshadowing.12 The novel itself consists of 14 chapters (titled with letters from A to N), each in turn divided into alternating perspectives, with some being only one or a few paragraphs long. Narrated retrospectively and almost exclusively in indirect speech, both the preliminary events leading up to the incident, the night of the alleged rape as well as the following weeks are meticulously traced, with the multiperspectivity sometimes revealing logical contradictions in the perception of the characters. So, for instance, Anna and Jonas seem to have different memories about how they met each other in the first place (5ff.) or different judgements of their first night together (19ff.).

Thus, the narrative tension does not revolve around the question of who the perpetrator is,13 but whether Jonas actually raped Anna—with the core point of friction, obviously, being that fateful night in the summer of 2016. The novel first presents Anna’s account of what she calls »›die Sache‹« (51), when she remembers:

Dass er ihre Arme nach unten drückte. Dass er versuchte, sie zu küssen, sie drehte den Kopf weg. […] Hielt sie fest. Sie wehrte sich, es tat ihr weh, als er in sie eindrang, sie war verkrampft, Tränen liefen ihr Gesicht herunter. Dann erst begriff sie: Er war stärker als sie. Sie konnte sich nicht wehren. Sie gab auf. Versuchte, sich zu entspannen. Dann tat es weniger weh. Fing an zu zählen. Seitdem wusste sie, dass 1380 Sekunden 23 Minuten sind. (61)

It is only a few pages later—and the choice of order actually might influence the reader’s perception psychologically (Hartner 2014: 359f.)—that the alternative perspective is presented:

Dass er sich nicht mehr an jedes Detail des Geschlechtsverkehrs erinnerte. Er war ziemlich betrunken, aber es war einvernehmlich, schließlich benutzte er ein Kondom! […] Anna hatte keine Ablehnung signalisiert, selbstverständlich hätte er ihren Willen akzeptiert, wäre es anders gewesen. Außerdem hatten sie sich bereits auf dem Spielplatz geküsst, dafür gab es mehrere Zeugen, und es zeigte, dass Anna da schon freiwillig gehandelt, und er sie zu nichts gezwungen hat. (87)

In denoting the »semantic clashes between different characters« (Hartner 2014: 354), the novel’s multiperspectivity thus mirrors the classic ›he said, she said‹ story, and the contrasting perspectives and different angles result in an overall picture that is more blurred than definitive. But it is precisely the very ambiguity of multiperspective narration that opens up the possibility of contrasting these fragments of memory and playing through different outcomes within the novel: On the one hand, for example, the social repercussions and stigmatization of (possible) false allegations as well as the psychological pressure of the police investigation (138f.; 146); on the other hand, the traumatic memories and the feeling of shame, Anna’s perception of guilt, her struggle for a self-determined way of dealing with the violence experienced, and even speculations about her sexual reputation in Anna’s own circle of friends (127f.; 141f.).

The end of the novel, however, remains disillusioning, as the criminal charges are dropped: Jonas is acquitted because he (technically) didn’t use physical force and Anna did not defend herself ›sufficiently‹ during the rape (162).14 However, by refusing a happy ending, the novel may seem more realistic and in line with the actual conviction rates of sexual assault and rape, which are statistically lower than other crimes. But that is not the only reason why reading the novel can have a cathartic effect: With its documentary compilation of different perspectives and classic narratives, as well as the playing out of a (fictitious) case history, nichts, was uns passiert makes it possible to experience an exemplary (and frighteningly, as marked by the title, everyday) »#MeToo« case through all stages.

2.2 Female Empowerment

Undoubtedly, literary and cinematic depictions of female experiences of sexuality and sexual violence both help to create a public awareness and mirror the heightened interest in addressing sexual harassment or inappropriate behavior. Nevertheless, in many texts—even if this may correspond to the statistics and hence appears closer to everyday life—the woman still remains in the very role of a victim that the »#MeToo« movement is repeatedly accused of creating and reproducing.15

This is where recent novels, films, or performances come in, allowing women to become the subject of their own stories,16 or even to search for an artistic way to process the traumatic violence—as, for instance, in a controversial performance by Emma Sulkowicz: As a junior student at Columbia University, she filed a complaint under Title IX with the school’s »Gender-Based Misconduct Office« and later with the NYPD, alleging she had been raped by a fellow student in 2012. But after her reports were ultimately turned down, and the university found the alleged perpetrator »not responsible« (Projansky 2018: 136.), Sulkowicz decided to reprocess the incident in a performance project for her senior year thesis under the title Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight): For several months, she carried a 50-pound dorm-mattress around campus in order to draw attention to her own case and to intervene »in a broader cultural and political debate about rape culture« (Banet-Weiser 2019: 167), three years before »#MeToo« even became a global hashtag.17

Similarly, literary texts too discuss (im)possibilities of transforming trauma into self-empowerment, for instance by referring to the ›rape and revenge‹ genre18 or simply by choosing a first-person narrative instance: The telling of one’s own perspective can both have a self-empowering effect and lead to trauma coping, for instance in Rosie Price’s debut novel What Red Was (2019).

Here, two different women share the same traumatic experience: The successful film director Zara became the victim of assault at the begin of her career, while the young Kate, a friend of her son’s, was raped by a fellow student. In analogy to the differences in the literary depiction—in contrast to the re-narration filtered by Zara (Price 2020: 236f.), the more recent sexual violence against Kate is described in detail by the omniscient instance (95ff.)—the two women have also developed individual strategies for dealing with the experience: Kate confides her story of rape to close friends only, without sharing any specifics of date, place or name but the rapist’s distinctive tattoo. Zara, on the other hand, makes the experienced rape the subject of her latest movie titled Late Surfacing with the female victim killing her rapist on screen in a proper »desire for symmetry that propelled this penultimate act« (374). But while Zara can thus symbolically complete her coping process after the death of her actual rapist (due to old age, not a murder),19 Kate would reject such an absolute closure:

But the problem was that now that the final retribution had been committed, now that the balance had been restored, there was no longer a cause: This woman had brought her story to too neat a conclusion, her existence so narrowed by rage that there was no longer any reason for her to continue to live. (374)

After all, the traumatic experience has involuntarily become an indelible part of Kate’s biography that she apparently, despite everything, does not want to simply erase: »›I wear it, I feel it every day. It’s under my skin, in my flesh‹« (275). It therefore comes as a shock for her when Zara’s film depicts the rapist having a tattoo—thus exposing Lewis as Kate’s actual rapist to her friends at the film premiere. For Kate, this unexpected revelation represents a severe transgression of boundaries that deprives her of the opportunity to decide for herself how to deal with the traumatic experience. Instead, Zara has appropriated the »most private piece of her history« (343) without consent (348).20

Therefore, despite her struggle of coping with the distressing memories,21 Kate seeks to embrace the pain, for instance when she two years later returns in a self-imposed shock therapy for the first time to the scene of the crime in an »act of self-determination« (337):

The smell of aftershave, the burden of an immovable weight. That red ribbon, that rawness. But they did not undo her. […] There would be other shades of red, other filters through which she could apprehend the world, and she would be more powerful for her knowledge of them. (339)

United in their traumatic experiences, the two women thus stand for two different forms of self-empowerment—the cinematic revenge in Zara’s movie as a symbolic act on the one hand, in contrast to Kate’s individual overcoming of trauma on the other. But they also differ on issues concerning individual responsibility. Zara remarks that being silent would not only protect the perpetrator, but potentially jeopardize other women as well. In contrast, Kate once again has a more individualistic, even fatalistic understanding, stating: »›It’s his responsibility to stop, not mine. […] It’s not my problem‹« (325). By simply comparing these positions without evaluating them, the novel leaves open which approach could be more ›feminist‹ or morally ›appropriate‹, and whether their different ways of dealing with both the (highly personal) traumatic experience and the social environment of ›rape culture‹ may, as sometimes assumed, be evidence of a generational shift (Noll 2020: 12).

Using the possibilities of fiction, the novel can show alternative options, play through different courses of action, and weigh them against each other, with its range of male and female characters—besides the victim and the perpetrator, for instance, voluntary or involuntary accomplices or the ›silent majority‹—making the readers think about how they would behave in that very situation: Thus, novels or movies simply can, in contrast to theoretical essays or lectures, be more powerful and reach a wider audience.

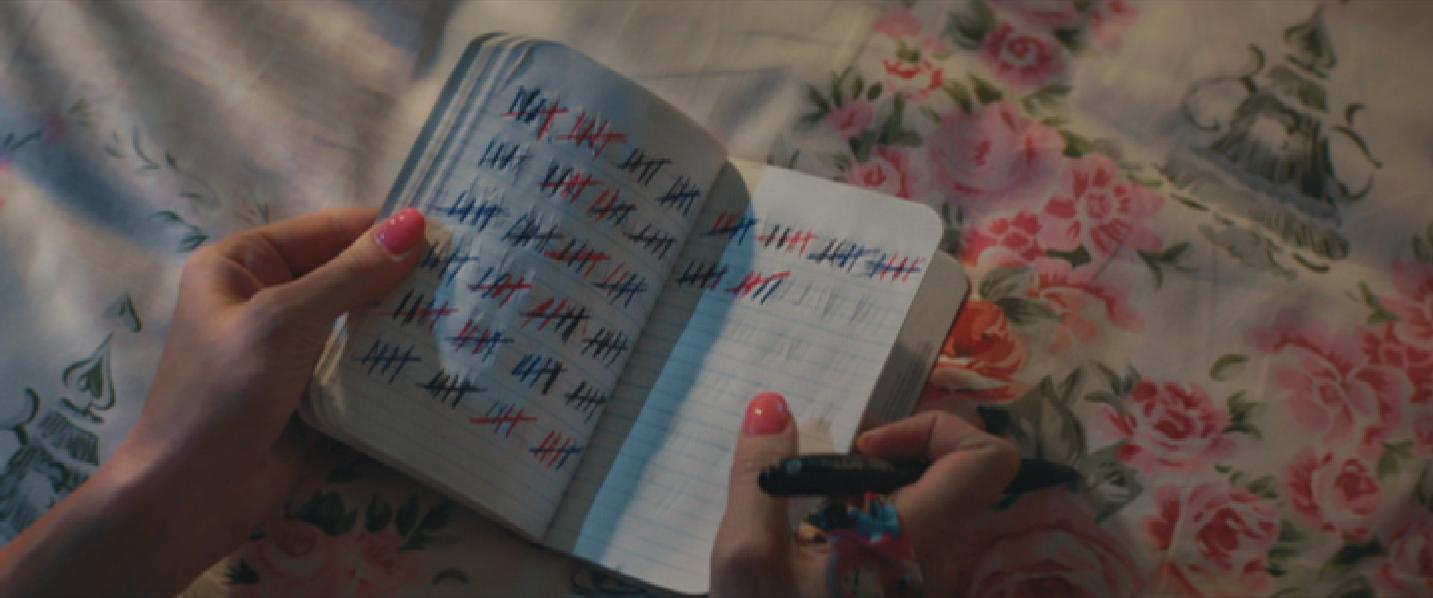

A case in point is Emerald Fennell’s directorial debut film Promising Young Woman with a spectacular 110 wins and 171 nominations, including the 2021 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (»Awards« 2021). The titular woman, Cassandra ›Cassie‹ Thomas (played by Carey Mulligan), drops out of medical school after the rape and eventual death of her friend Nina Fisher, thus quitting a ›promising‹ career as a future doctor and instead working at a local coffee shop. After her shifts, she roams around bars and clubs and poses as drunk ›bait‹ in order to be picked up by men taking advantage of her. At their homes, she reveals herself as sober and confronts them, with the cases later being collected as tally marks in her notebook (Fig. 3).22

One day at the coffee shop, Cassie coincidentally meets her former classmate Ryan Cooper, and they begin dating; by now, Ryan has not only become a doctor, but also Alexander ›Al‹ Monroe, who allegedly raped Nina at the time and who is soon about to marry his fiancé. This encounter sparks Cassie to embark on a full-blown revenge in three parts with each ›chapter‹ being introduced by a tally mark inserted on screen: She first meets her former fellow student Madison McPhee, who blames Nina’s »reputation for sleeping around« (00:37:43 min.) for the assault; during their meeting Cassie first gets her drunk and then arranges for her to wake up in a hotel room next to a stranger. In the second chapter, Cassie visits Elizabeth Walker, the dean at the time who had dismissed the reported rape allegations against Al Monroe as »too much of a ›he said, she said‹ situation« (00:43:52 min.). Again, Cassie implements a cathartic shock therapy, claiming that Walker’s young daughter is momentarily exposed to the same situation Nina was in—in a dorm room with drunk students. Finally, Cassie targets Jordan Green, Al’s former lawyer, who pressured Nina to drop the charges. But it comes as a surprise to Cassie that he immediately breaks down tortured by guilt, and begs her to forgive him.

Cassie’s secret revenge plan has come to an end, and nothing seems to stand in the way of a future together with Ryan—at least until she receives a video file of the night in question, and now not only obtains (visual) evidence of Nina’s rape, but also has to learn that Ryan was one of the bystanders and did not intervene. She immediately breaks up with him, and Cassie’s revenge plot is expanded by a fourth chapter, in which she arrives at Al Monroe’s bachelor party dressed as a stripper: After drugging the other friends, she handcuffs him to a bed and confronts him with the video evidence. As he continues to vigorously deny the rape, Cassie wants to permanently mark him by tattooing Nina’s name on his torso.23 Suddenly, Al manages to free his left arm and overpowers Cassie—and in an agonizingly long death struggle that lasts several minutes, he ultimately kills her.

And so the film does get a fifth chapter (in accordance with the classical drama structure), although it remains open whether it would be the catastrophe or a redemption: Ironically underscored by Juice Newton’s Angel of the Morning of all songs,24 Al’s wedding ceremony comes to an abrupt end when police officers arrest the groom for murder (Fig. 4), after Cassie had protected herself in advance by making the lawyer Jordan Green her accomplice, who turned over evidence of Nina’s rape and Cassie’s disappearance to the authorities.25

Perhaps we need these powerful images, the surprising twists and a radical, hardly predictable ending to make the film cathartically remain in the memory of the audience—and thus actually make a change in society. In this way, Promising Young Woman indeed plays through different »#MeToo« narratives, but above all, with male complicity and what Linda Gordon in her 1981 essay The Politics of Sexual Harassment already called »a powerful bonding among men« (Gordon 2018), the film strikingly brings a theme to the center of attention that questions the »#NotAllMen« counter-argument.26 On the other hand, however, it seems that the film does not really offer a practical solution that goes beyond the most existential self-sacrifice: Cassandra has to become an avenging angel with her own death being the final sacrifice to Nina.

2.3 Metafictionality

Besides its drastic approach, Fennell’s Promising Young Woman was also critically praised as a meta-commentary to the ›rape and revenge‹ genre (Lindemann 2021: 70), since the movie »befragt mit den Mitteln des Kinos das Kino selbst und die Rolle, die es beim Verharmlosen von Sexismus und Gewalt gespielt hat« (Pilarczyk 2021: 118). And indeed, it is striking that the very medium that stood in the epicenter of the Weinstein revelations is now becoming one of the most important and popular platforms for reconsidering the industry’s own behavior—from the reconstruction of factual cases to more abstract or allegorical stories.

Jay Roach’s Bombshell (2019), for instance, is based upon the actual 2016 sexual harassment accusations against the conservative media mogul Roger Ailes, the founder and long-time CEO of Fox News. The film ultimately achieved widespread attention due to both its high-profile casting—with Charlize Theron (as Megyn Kelly) and Nicole Kidman (as Gretchen Carlson) in the lead roles alongside supporting actresses Margot Robbie, Kate McKinnon and Allison Janney—as well as its main focus being on the women: Instead of retelling the rise and fall of Ailes himself (with the potential danger of creating a myth), the film examines the hostile work environment, the entrenched culture of sexism and the gender-based discrimination from the perspective of different female employees. However, the contrasting characters also show how differently the women deal with the toxic workplace around them, from mutual solidarity and support27 to playing by the ›rules‹ in hope for a career breakthrough.28

Showtime’s miniseries The Loudest Voice (2019), starring actor Russell Crowe as Roger Ailes, takes the exact opposite approach and depicts the Fox CEO as a paranoid strategist, who becomes increasingly delusional in the course of the seven episodes (The Loudest Voice, S1.E7, 00:10:41 min). This ›male‹ perspective, in turn, now depicts the abuse of power from the ›other‹ side, when taking the perpetrator’s point of view can thus trace back the origins of Fox’s corporate culture of complicity:

Ailes’s attitudes about women permeated the very air of the network, from the exclusive hiring of attractive women to the strictly enforced skirts-and-heels dress code […]. It was hard to complain about something that was so normalized. (Sherman 2017: 402)

Similarly, both Kitty Green’s 2019 film The Assistant as well as the first season of The Morning Show (2019), a popular Apple TV+ series, refer to factual cases, but without mentioning actual names.29 Thereby, the ubiquity of abuse within the film and television industry as well as the everyday quality of harassment in general becomes more apparent. The Assistant, for instance, mirrors the self-exploitation and the interchangeability of the assistant Jane (played by Julia Garner) through an agonizingly lengthy narration; the de-individualization even goes so far that Jane responds to abusive accusations of her boss with standardized e-mails (The Assistant, 00:16:27 min.; 01:00:42 min), or that her HR complaint is dismissed as she is »not his type« anyway.30

2.4 The Other Side

It may not have come as a big surprise to many critics that the balzacesque plot of Les Choses humaines in the tradition of the ›grands récits‹ of 19th-century French literary realism was awarded the 2019 »Prix Interallié« as well as the »Prix Goncourt des lycéens«: Karine Tuil’s novel, published by the prestigious Gallimard publishing house, hit a nerve in French society, which was torn between the urgent need to finally debate everyday sexism and harassment on the one hand, and on the other to preserve the ›galanterie française‹ as a cultural ›heritage‹.

Tuil’s novel is set in the higher circles of French society and revolves around the successful TV and radio host Jean Farel, his younger wife Claire,31 and their son Alexandre. The plot centers around two major events: First, an evening in the summer of 2016, when the veteran journalist Jean Farel is appointed to the »Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur« at the Palais de l’Élysée. The next day, the Farel family is surprised by a police raid in Jean’s luxurious Paris apartment following a complaint of rape: But the alleged victim is not—as the novel first indicates—the young colleague Jean has seduced the night before, but the 18-year-old Mila, the daughter of Claire’s current partner Adam Wizman, who was at a college party with Alexandre.

The second part of the novel is devoted to the court proceedings two years later:32 Over a good 150 pages, statements and protocols are put together; similar to the multiperspectivity in Wilpert’s novel discussed above, the readers are provided with a comprehensive paperwork of the trial against Alexandre, who strongly denies Mila’s rape allegations. But despite this documentation, questions arise concerning the factual accuracy of the opposing statements, the balance of the arguments brought forward or the neutrality of the compilation (which is obviously influenced by the court procedures, the quality of the lawyers etc.).

It is therefore telling that Mila as the victim has no agency of her own both throughout the novel as well as the hearings, and literally disappears from the story after the trial ends with a relatively light suspended sentence for Alexandre: Even though the title suggests a truth outside the gender binary, the human condition appears to be shaped by patriarchal structures and male hegemony.33 But Les choses humaines not only updates 19th-century theories of determinism, adding sex as a decisive factor to Hippolyte Taine’s categories of ›race, milieu, moment‹ (Taine 1863: xxiiff.), but also seems to stand in the tradition of French sociology: The novel outlines the current public discourse on sexuality—from the 2015/16 New Year’s Eve sexual assaults in the German city of Cologne34 or misogyny in internet pornography (90; 212) to the change in perception when suddenly one’s own family is affected, with Jean’s infamous testimony on the witness stand:

»Alexandre est une bonne personne, […] pourquoi je pense qu’il serait injuste de détruire la vie d’un garçon intelligent, droit, aimant, un garçon à qui jusqu’à présent tout a réussi, pour vingt minutes d’action.« (281)

Thus, by making the victim herself even more of an object in the literary perspective, the agonizing dominance of patriarchy is depressingly underlined; on the other hand, it is perhaps precisely through such a perspective that toxic masculinity can be unmasked.35

In a similar approach, Mary Gaitskill’s short story This is Pleasure, first published in the New Yorker in 2019, brings together two opposing perspectives—the male ›perpetrator‹ and the female ›victim‹—, but it quickly becomes obvious that such clear assignments of responsibility simply do not exist. The 22 chapters, each titled Q or M, alternate between the perspectives of the successful editor Quinlan ›Quin‹ Saunders and his former assistant and now good friend Margot: Considering himself both an extrovert and a sensualist, Quin loves to flirt rather explicitly and expects women to respond to his ›playful‹ teasing in a similar way. He also has a certain need to give advice, which is apparently (at least from his perception) very often embraced by women—but his lascivious way of flirting also includes, for example, asking women intimate questions or touching them in equally intimate places. If they comply with his ›desires‹, the female assistants receive access to Quin’s inner circle—otherwise he dumps them (42f.). Many years ago, Margot, too, was one of his ›victims‹—but when he inappropriately reached between her legs, she immediately put him in his place (12f.). Quin, in turn, is impressed by her strong self-confidence, and from now on mentors her.

Once again, the narrative technique of multiperspectivity is used here to shed equal light on both sides—but compared to Wilpert’s novel, the case in question is a different one, with the legal as well as moral boundaries being less clearly recognizable: Margot not only played along with his games and accepted Quinn’s favors; she also noticed the continuing unwanted advances and his inappropriate physical contact with other women and is repeatedly »mad« at him (33)—but ultimately seems to expect from them a resistance similar to her own (69).

After Quin is mentioned in an online petition among multiple other »abusers«, signed by hundreds of women (63) in the wake of the »#MeToo« movement—which is never explicitly named in the novel—and finally a lawsuit against his publishing firm is brought forward, he tries to explain his longing for a special intimacy: »›I flirted. That’s all it was. I did it to feel alive without being unfaithful‹« (61). Thus, Quin is not a ›typical‹ »#MeToo« case in the sense that he actually never raped a woman; yet being (as his wife Carolina puts it) a »›pinching, creeping, insinuating fool‹« (62), he takes advantage of the very same power imbalances in the workplace. Similarly, This is pleasure is not a typical »#MeToo« story either: In contrast to Tuil and the emphasis on patriarchal power, mirrored through the one-sided dominance of the perpetrator’s perspective, Gaitskill seems even more interested in psychologically tracing the man’s behavior and exploring moral gray areas.

3. Outlook

When »the silence breakers« of the »#MeToo« movement were named Time magazine’s »Person of the Year« in 2017, its editor-in-chief had a clear perspective of what’s to come next: »Indeed, the biggest test of the movement will be the extent to which it changes the realities of people for whom telling the truth simply threatens too much« (Felsenthal 2017: 21). About four years later, the movement is far from being over, when 2021 saw, among other things, the resignation of New York governor Andrew Cuomo as well as new initiatives like »Deutschrap MeToo«.36

This overview of the past (and at the same time first) four years of the »#MeToo« movement thus only remains a baseline study. And like any other social discourse, the debates will change, and new narratives and counter-narratives will enter public discussion over the years to come (Foucault 1971: 4f.). Each narrative thereby ›tells‹ stories to both structure the complexity of the discourse—classically through plots (good/evil, right/wrong) and protagonists (subject/object, perpetrator/victim)—and to reduce it to central issues. In addition to their function of order, however, narratives also serve to activate and mobilize, since they are associated with a clear (political, social) orientation as well as (implicit or explicit) guidance for action.

Since the movement’s beginnings in October 2017, both press coverage and social media have been the central fields of discourse in which social, legal, and feminist issues are being negotiated with reference to individual figures and personal stories. Both the authenticity of these narratives and the broad generalizability of the highly individual incidents establish a political activism with global applicability, but inevitably also lead to an anti-feminist backlash with specific counter-narratives (such as the five examples identified above). The discursive arena of the internet in particular constitutes a special feature in this context: Although the discussions can now be conducted in real time across continents and time zones, many of the narratives experience a strong shortening and thus a further polarization.

On the other hand, »#MeToo« also continues in literature, film and other popular media with empowering stories and critical perspectives, by using fictional stories in order to denounce injustices and point out possible solutions:37 Chandler Baker’s novel The Whisper Network (2019), for instance, deals with women’s resistance against their sexist, abusive boss, and their fight against a work environment which forces female employees to erase their »femininity in just the right ways« (Baker 2019: 373); collections of stories, such as the anthology Sagte sie (2018), edited by Lina Muzur, bring together female voices and thus help to establish a diverse canon. On the other side of the spectrum, perpetrator perspectives might appear morally problematic, but do expand the literary »#MeToo« discourse, for instance by deconstructing the male dominance of a figure such as Harvey Weinstein in David Mamet’s Bitter Wheat (2019). In a similar way, Emma Cline’s short story titled White Noise (2020) depicts a broken Weinstein on the day before the jury verdict—and thus on his last day in ›freedom‹—who mistakes a neighbor for the novelist Don DeLillo and fantasizes about his comeback as a film producer.38

These are neither ›easy‹ nor ›simple‹ stories, and ›right‹ does not always triumph over ›evil‹. But in contributing to the debate, novels, films or performances can indeed broaden the »#MeToo« discourse by playing through exemplary stories or by even taking radically different perspectives. And through their search for new aesthetics and diverse narratives, writers, filmmakers and performers alike do not allow themselves to be silenced either.

Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Thus, for instance Nathan Zuckerman, the social observer and chronicler of Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain (2000), describes the early 2000s, the years »when terrorism—which had replaced communism as the prevailing threat to the country’s security—was succeeded by cocksucking« (Roth 2016: 2), as an era marked by an »ecstasy of sanctimony«. Similarly, Chip Lambert, the protagonist of Jonathan Franzen’s critically acclaimed novel The Corrections (2001), quotes the infamous sentence when he himself is terminated as a college professor following an inappropriate sexual relationship with the student Melissa (Franzen 2017: 90). 2 In the main evening news edition of the German Tagesschau, Strauss-Kahn was characterized as »ein starker IWF-Kapitän mit einer bekannten Schwäche für die Damenwelt« (Tagesschau, 15 May 2011, 01:47 min.). And even Ségolène Royal, a minister of family and children under President Jacques Chirac from 2000–2002 and a promising Socialist Party candidate for the 2012 election herself, said in a first statement: »Ma pensée en cet instant va à sa famille, à ses proches et aussi à l’homme qui traverse cette épreuve.« (qtd. in Liberation) In her later memoirs, however, she harshly criticizes the French political sphere as a hostile environment for women: »Les femmes sont depuis longtemps considérées comme des intruses en politique.« (Royal 2018: 23). 3 The document (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/u/1/d/1Z95WVLLbh6M1U_Ch4vbfKuJtUmznu-ZgM9yHFBJl68I) was posted by Argento on 7 November 2017, but is meanwhile deleted. 4 Tweet from 13 October 2017, https://twitter.com/LettreAudio/status/918885763764408321 (last accessed: 31 October 2021). 5 So far, her post (https://twitter.com/Alyssa_Milano/status/919659438700670976) has more than 21k retweets and 48.5k likes (last accessed: 31 October 2021). 6 Obviously, conviction rates of about 8% in Germany or 7% in the UK (Hohl/Stanko 2015) by far do not mean that the claims are untrue, but indicate instead that the alleged assault simply is not legally provable in a court of law with different perceptions of the incident and one person’s word against another’s (»he-said/she-said case«) or with not enough ›hard‹ evidence to support the claims. 7 The touring exhibition »What Were You Wearing?«, developed by the University of Kansas’ »Sexual Assault Prevention and Education Center« and first shown at the University of Arkansas in 2014, displays individual stories of sexual assault victims next to the outfits they were wearing when it happened: »The art installation ›aims to shatter the myth that sexual violence is caused by a person’s wardrobe‹, and includes t-shirts, exercise clothes, dresses, and cargo shorts« (D’Amore 2021: 95). 8 The hashtag »#Aufschrei« (›outcry‹)—the reaction to a journalist denouncing sexist comments made by a German politician (Himmelreich 2013)—was initiated by Anne Wizorek on 25 January 2013 to raise awareness for everyday sexism, but her post (https://twitter.com/marthadear/status/294586884540223488) only had a low reach on Twitter at that time (last accessed: 31 October 2021). 9 After a montage of ›toxic masculinity‹, including scenes of mobbing, misogyny and physical transgression, the commercial shows examples of men holding other men accountable and stepping in for those who are bullied or harassed; cf. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPmuEyP3a0 (last accessed: 31 October 2021). 10 This idea of seduction is well established within the western canon, for instance when in Ovid’s Ars amatoria both forceful kissing—»illa licet non det, non data sume tamen«—and even rape—»grata est vis ista puellis«—are belittled in satisfying male desire (Ovid 1957: 58f.). 11 In 2021 it was revealed that Cat Person not only corresponded to experiences of many women all around the world, but that the short story is itself based on actual events, retold by Roupenian without ›consent‹ (Nowicki 2021), thus provoking discussions about the limits of fiction in general (Franzen 2021: N3). 12 Only very rarely, the narrative »I« appears overtly, for instance with remarks such as »hakte ich nach« (Wilpert 2018: 40) or »fragte ich« (97). 13 In classic crime and detective fiction, this would be the »whodunit« plot. 14 In 2016, the sex crime law in Germany was finally tightened with the embedding of the principle of »no means no« in criminal law. 15 Cf. chapter 1.2.1 before. 16 In Kate Reed Petty’s novel True Story (2020), for instance, Alice counters the ›rumors‹ (Reed Petty 2020: 65) about her being the victim of a sexual assault she does not remember by appropriating the story in her ›own way‹ and thereby gaining discourse power: »I made it a thriller, a horror, a memoir, a noir. I used my college essays, emails, and other documents to ground the story in the truth—they’re the closest thing I have to ›evidence‹, proof that my memories, however few, are real« (322). 17 In 2015, Sulkowicz ›recreated‹ a sexual assault encounter in her eight-minute video Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol (2015), with the title referring to the famous René Magritte painting La trahison des images (1929) and the general ambiguity of (artistic) reproductions: Uploaded on her website (www.cecinestpasunviol.video) (last accessed: 31 October 2021), the disturbing video both hints at the unrestricted availability of ›hardcore‹ pornography on the internet and at the same time addresses the transition from consensual to non-consensual sex. 18 However, recent films from Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge (2017) to Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel (2021) are sometimes criticized for being under the influence of a »long arm of the male gaze« (Posada 2020: 193) instead of developing ›other‹ narratives and gazes (Herrmann/Klocke 2020: 70f.). 19 In a conversation with Kate (»›mine is dead‹«), she regrets that she never confronted her rapist: »›So it really is too late; I have no outlet, no living cause. It’s all buried, and now that I’m here to excavate it, it’s too late to really matter‹« (322). 20 This is an interesting parallel to the actual debates about the fictionality of Roupenian’s Cat Person before. 21 The novel only briefly addresses, through its omniscient narrator, that Lewis himself—despite denying the rape to his friends as consensual intercourse (359)—is also haunted by (traumatic) images of the incident (319). 22 However, the meaning of the colors black and red used for the lines as well as the names remains unclear. 23 [1] In a similar act of symbolic ›revenge‹, Lisbeth Salander brands her rapist by tattooing on his stomach in Stieg Larsson’s 2005 novel Män som hatar kvinnor (Larsson 2008: 287f.). 24 Promising Young Woman deliberately plays with (genre) expectations and is thus able to create an ambivalent feeling—from the poppy soundtrack or the modern update of the ›final girl‹ as a classical trope in (horror) movies to the deliberate counter-casting with the roles of the perpetrator and the hangers-on being played by familiar ›nice guys‹ from films and TV series such as Private Practice (Chris Lowell as Al), Funny People (Bo Burnham as Ryan) or New Girl (Max Greenfield as Al’s best man). 25 Thus, the connection to the mythological name Cassandra is fulfilled after all. 26 Similarly, in Wilpert’s novel, Jonas was also described as »einer von den Guten« (Wilpert 2018: 111). 27 Almost resignedly, Meghan remarks at one point to Kayla: »We find each other.« (Bombshell, 01:17:49 min.) 28 In an impressive scene, the steadicam follows various women through the dressing rooms: While they defend Ailes on their phones to journalists, they squeeze into tight dresses, short skirts and push-up bras at the same time (Bombshell, 01:10:56 min.). 29 The character of Mitch Kessler (played by Steve Carell), for instance, seems to have been inspired by popular TV hosts such as Charlie Rose (the co-anchor of CBS This Morning) and Matt Lauer (co-anchor of the Today Show on NBC), who were fired amid allegations of misconduct and sexual harassment in November 2017. 30 The Assistant, 00:57:29 min. 31 Claire Davis-Farel too is a respected journalist; interestingly, she is introduced to the readers as having been one of three female interns during the second Clinton administration, along with Monika Lewinsky and Huma Abedin (Tuil 2019: 17f.). This blending of real persons and events with fiction becomes programmatic for the whole novel itself; at the same time, such references to the actual cases of Lewinsky and Abedin underline that a regular culture of sexual assault existed long before the recent »#MeToo« movement. 32 The third chapter, entitled »Rapports humains«, seems like an obvious reference to Honoré de Balzac’s Comedie humaine and its universal ambition of »l’histoire et la critique de la société, l’analyse de ses maux et la discussion de ses principes« (Balzac 1976: 16). 33 Besides the alleged rape, the male power over the female body is probably best illustrated by Jean’s pressure on Alexandre’s former girlfriend to have a late-term abortion (Tuil 2019: 105; 113). 34 Claire has repeatedly discussed the incidents, claiming that »›les femmes agressées doivent être écoutées et entendues‹« (39), and assuming »›une chosification de la femme qui mène aux violences commises sur son corps‹« (138) as a cause. 35 Though the novel ends with Alexandre becoming a successful app developer (users of »Loving« can search for partners for sexual encounters via the app in a customized way, and then give consent for currently desired sexual preferences and practices), in the last scene he is ironically dumped after an unconsented French kiss: »Dans la cuisine, son téléphone vibra: d’un clic, elle avait annulé son consentement« (Tuil 2019: 341). 36 Following assault allegations against a German rap artist, topics of misogyny, sexism and sexual violence in rap music were—to that extent for the first time—publicly discussed in Germany over the course of the summer of 2021. 37 The artistic focus is still predominantly on Europe and North America, although exciting approaches from other parts of the world are gradually becoming available—for example with an innovative portrayal of rape trauma in the Taiwanese film Nina Wu (2019), which is also meta-reflexively set in the movie industry itself. 38 Here, Weinstein plans a film version of DeLillo’s 1985 novel White Noise, but ironically confuses the book’s first sentence (»The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the west campus.«) with the beginning of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), another great and equally ›un-filmable‹ work of 20th century American literature (Cline 2020: 52; DeLillo 2012: 3; Pynchon 2013: 3).